MORE POWER TO INDIA

With a population of 138 crore (1.38 billion) people, a large percentage of whom do not have access to basic individual and societal needs such as clean water or a roof over their heads, independent India’s 73-year-old developmental journey requires continued heavy and multidirectional investment. And in a developing country, prioritising investments can never be easy for a government! Additionally, developmental planning and investment must account for the rate of population growth.

Below graph shows the percentage increase in populations for some countries. India has doubled its population since 1971. South Africa and Bangladesh have more than doubled theirs although in terms of size of population, they’re both small fractions of India’s.

India’s power consumption journey

Undoubtedly, in less developed countries making basic human needs available to more and more of their populations is a high priority for governments. However, underinvestment in socioeconomic building blocks such as primary education, highways, telecommunications, power generation & transmission slow down a country’s pace of progress, and consequent improvements in quality & standards of living. Taking the specific case of power, on one hand per capita power consumption is an indicator of how developed and prosperous a country is, on the other, power is an enabler for increasing literacy, education, safety and availability of healthcare. Diving deeper into India’s power consumption trends provides some interesting insights.

Below is the graphical representation of India’s percentage per capita power consumption increase, under Union governments in power since 1980. The governments headed by VP Singh and Chandrashekhar between 1989 and 1991 have been represented as one.

The Rajiv Gandhi-led government in the 1980s delivered an impressive increase in per capita power availability by the end of its term in 1989. If prorated to five years, the subsequent two governments together lasting about 1 ½ years (1989-1991) also fared well on this front, the PV Narasimha Rao-led govt not as well in comparison. Six years of Atal Behari Vajpayee-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) too delivered a low increase of 17%. For all its flaws, United Progressive Alliance (UPA) registered impressive increases of over 30% during each term. The biggest jump in per capita consumption has been under the present Narendra Modi-led NDA government.

Although per capita power consumption has increased over the decades, thanks in varying measure to every government in power, availability of power has been spread unevenly across the country. Even 50 years after India’s independence the definition of rural electrification was very limiting. Up till 1997, a village was classified as electrified if electricity was being used within its revenue area for any purpose. In that year the definition was extended to include availability of electricity in the inhabited locality within the revenue boundary of the village, for any purpose. However, this still meant that much of rural India’s population continued to be deprived of power in key utilities and their homes. In 2004 the definition of rural electrification was broadened further to include its availability in basic infrastructure in inhabited localities, in public utilities such as schools and health centres, and at least 10% households in a village. Based on this definition, in April 2018 NDA achieved the significant milestone of making electricity available to every village in India that had been deprived of it since Independence. This was recognised by International Energy Agency as “one of the greatest achievements in the history of energy”.

In spite of the achievements of the present and previous governments, India has a long way to go before every household across the country is electrified and has reliable supply. Daunting as this dream is, it’s also an evolving one. As literacy levels and employment opportunities are increasing, aspirations and standards are rising, growing the demand for reliable supply of electricity.

How much power does India need?

For a goal such as universally available electricity, it is difficult to quantify India’s per capita power needs. In absolute numbers, India was at 804 kWh in 2014, USA was at nearly 13000 kWh, Indonesia at 811, South Korea at 10496 and South Africa at 4197 kWh. Which one of these should be India’s goal? The Union Power Minister has taken the approach that India aspires for equalling the current world average, which is three times India’s current per capita consumption.

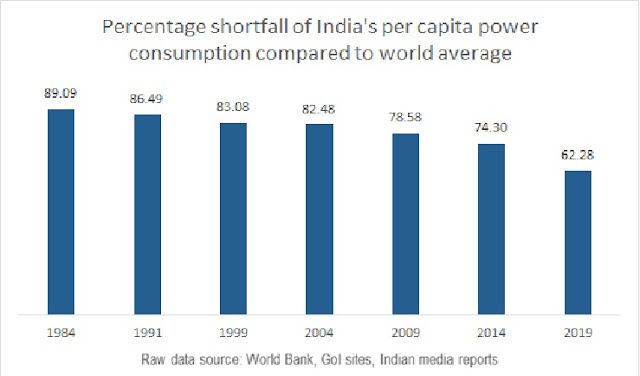

With the world average as its objective, retrospectively, in 1984 India’s per capita consumption was about 10% of the (then) objective. Consumption in 2019 was much better but India was still 62% short of its aspirational level. And given how much time it has taken us to reach the modest consumption of about 1100 kWh in 2019, we have a long way to go. Governments today and in the future do not have the luxury of underinvesting in key infrastructure like power. Given its track record over the last six year, one hopes for continued focus by the present Union government for the rest of its term.

Power Loss and Theft

According to Central Electricity Authority, over 27% of power generated in India is lost either by dissipation or by theft. According to a report published in the same month (Jul-18), 22% is lost in dissipation. In late 2019, according to the Union Power Minister, power loss by distribution companies over 2018-19 stood at 18.5% suggesting an improvement from the previous year, although this figure too translated to a loss of INR 27000 crores. The Union govt aims to reduce losses to 15% by late 2021, but the journey still has many more steps. From being among the highest power losing countries, India needs to at least reach the world average of under 10%.

Besides power loss, India is also addressing its theft at national and state government levels. In 2019 a campaign by the govt of Rajasthan helped its power distribution company earn INR 91 crores in fines and revenues over five months. The Uttar Pradesh govt in 2019 posted 650 policemen to protect Power Corporation staff while they’re attempting to check power theft. In Delhi where power theft is estimated to cost distribution companies INR 400 crores (4 billion) annually, the state government has cracked down on the activity, leading to 5500 complaints and the arrest of 2500 people over 18 months. For the Prime Minister’s constituency of Varanasi, underground cabling has helped bring down theft. It is also a safer option than overhead ones, besides having aesthetic value. While underground cabling by city and town across the country will be an expensive and longer-term project, the Union government has prioritised installation of smart meters across the country – an initiative aimed at improving both billing and collection, benefiting the bleeding distribution companies as well as legitimate consumers.

The future – thermal, hydro, renewable sources of power

Per capita power consumption of several countries plotted over four decades shows India as very close to the lowest (only Bangladesh among compared countries is lower).

While India needs substantially greater availability of power for its population, rising to the levels of even South Africa (about four times greater consumer than India) will have to be carefully planned, balancing growth aspirations and social initiatives with responsibilities towards the environment.

At present thermal power generation in India stands at nearly 62%, while hydro and nuclear are at 12.2% and 1.8% respectively. In the just-concluded year thermal power generation was reduced by 2.75%, hydro increased 15.48% and nuclear by 22.9%. India aspires to increase its present clean energy generation capacity from the present 135 GW to 220 GW in 2022 – an increase of over 60%. Further, India aspires to have 60% of power generation from clean sources by 2030.

From bold investments to improve collections by distribution companies, to steadily increasing power generation while maintaining regard for the environment, India may have taken right steps in the right direction in the past too, but the pace is quicker today, which is long overdue! Over the next decade or so one hopes to see these investments benefit Indian masses in terms of greater availability of healthcare, primary education, safety, employment opportunities and a general uplift of living standards.

Comments

Post a Comment